Science Revision Tips for GCSE and A-level Students from a Cambridge Graduate

About the author

Philippa Logan read Natural Sciences (specialising in Chemistry) at Newnham College, Cambridge.

Hermione Granger was essentially doing science A-levels.

Except in her case, they were NEWTs (Nastily Exhausting Wizarding Tests), and instead of doing the conventional Physics, Chemistry and Biology, she was taking more intriguing subjects: Ancient Runes, Arithmancy, Charms, Defence against the Dark Arts, Herbology, Potions and Transfiguration, to be precise.

And, being Hermione, she did very well. Meanwhile, Harry and Ron didn’t take NEWTs at all – partly because they were busy looking for Lord Voldemort’s Horcruxes and thus saving the world. Fair enough.

So, what was the secret of Hermione’s success? Native intelligence? Yes, partly, because she was clearly a bright student and eager to learn. But she also hinted at a revision technique, which included a revision timetable. It has to be said that there is not much evidence for Harry’s and Ron’s revision technique – merely a lack of it.

And here we are getting relevant. If Hermione Granger can do it, so can you.

Revision literally means ‘re-vision’ – looking at something again. Which means that you must have seen it in the first place.

Spider diagrams

There are lots of different ways of writing out your notes. Obviously, you can just copy them out, in shortened form, from your exercise book – perhaps highlighting the important parts, or different topics, in different colours.

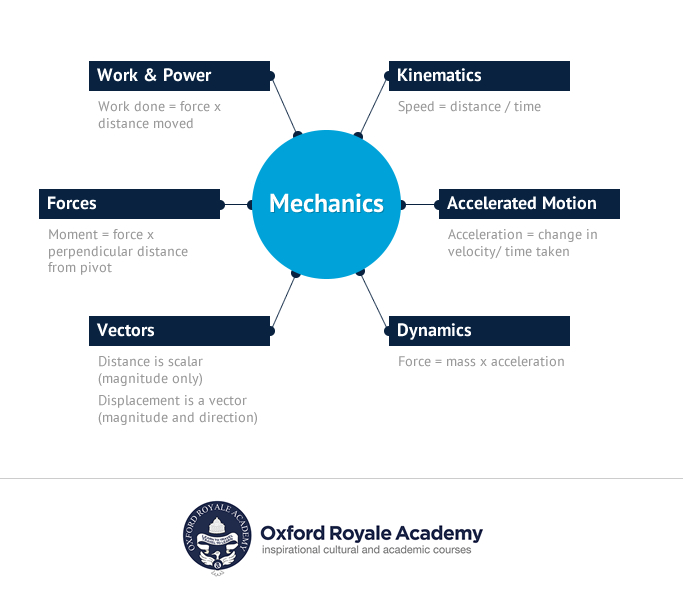

But have you come across spider diagrams? These can be a handy way of forcing you to get something straight in your mind before you write it down on the page. Here is an example:

You put the topic in the centre of your page. Let’s say you’re doing Physics, and you’re looking at Mechanics.

So, write down Mechanics in the centre of your page. Now, what are the sub-topics here? To make it easier, you can go by the chapter headings in your text book. Kinematics, accelerated motion, dynamics, vectors, forces, work and power. Write these sub-topics like the legs of spider (let’s not take the analogy too far – there probably won’t be eight legs here). Then under each sub-topic, write down the most important points, and the things you need especially to remember. These might be equations, or definitions, or little sketches about how to work out problems.

With a spider diagram, you can get everything you need to know about a whole topic on a single sheet of paper. It’s very satisfying. Well, not everything you need to know, of course, but a jolly good summary. Once again, if you take the time to do this properly, it forces you to make sure you understand each mini topic as you write it down.

Understand before you revise

Make sure you understand something before you start revising it, otherwise you risk learning something that’s not correct. The best way to do this is to understand new information as you go along. You’ll know from your homework whether you have got to grips with a subject. If you haven’t, then ask the teacher, or a friend who does understand the subject, or go to a science clinic, if your school offers one – and get clear in your mind what you haven’t been able to understand.

Revision need not be daunting. Some find it boring and tedious, and resent having to set aside long swathes of time at a desk when there are more exciting things to be doing. One of the keys to effective revision is to make sure that you have enough breaks from revision, to make sure that you do get to do those exciting things. And by ‘exciting’, I’m only talking in relative terms: exciting in comparison with revision, which might mean a chat with your friends, a cup of tea, or a few minutes harassing the dog, and not necessarily going off to fight the demons of the spirit world.

Draw up a timetable

So, you know you are going to have breaks during your revision. Now think about writing a revision timetable. It doesn’t work for everyone, but it can be helpful. At least it can help you keep track of how much revision you have done, which can be a confidence-booster.

Let’s say the holidays are coming up. Your school may well have suggested a number of hours of revision that you should aim for. Some schools suggest a ridiculously high figure – but revision is not a 9-5 job, and it’s counter-productive to aim to do too much.

Think about what’s possible for you. Think what’s realistic, without being a slave-driver or overly lenient. Could you manage six hours a day? No? Four or five hours? If you start at 10 o’clock, you can do two and a half hours before lunch, and then two and a half hours in either the afternoon or the evening – leaving the rest of the evening or the afternoon free.

And if you don’t normally get out of bed that early in the holidays, try and make a point of doing so. Have a lie in for the first day or two, but then let the discipline kick in, and make sure you get up in time to get down to work at 10am. Write it on your timetable, to help you stick to it.

If you’ve decided that it will help to have a revision timetable, it’s worth spending some time drawing it up. This may seem an awful faff, but it IS worth spending time up front to work out what you are going to be doing, and how much, and when.

Sample revision timetable

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | |

| 10-11am | Topic 1 | Topic 7 | Topic 13 | Topic 19 | Topic 25 | Topic 31 | Day off |

| 11 Have a 5- or 10-minute break | Break | Break | Break | Break | Break | Break | – |

| 11.10-12.10 | Topic 2 | Topic 8 | Topic 14 | Topic 20 | Topic 26 | Topic 32 | – |

| 12.10-12.40 | Topic 3 | Topic 9 | Topic 15 | Topic 21 | Topic 27 | Topic 33 | – |

| Lunch | Lunch | Lunch | Lunch | Lunch | Lunch | Lunch | – |

| 2-3pm | Topic 4 | Topic 10 | Topic 16 | Topic 22 | Topic 28 | Topic 34 | – |

| 3pm Have a 5- or 10-minute break | Break | Break | Break | Break | Break | Break | – |

| 3.10-4.10 | Topic 5 | Topic 11 | Topic 17 | Topic 23 | Topic 29 | Topic 35 | – |

| 4.10-4.40 | Topic 6 | Topic 12 | Topic 18 | Topic 24 | Topic 30 | Topic 36 | – |

| Freedom! | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Above is an example of a timetable for five hours of revision a day. Make sure you have either one or two days completely free each week – or one day that you definitely always have off, and the other day as ‘spare’, in case you have to rearrange some of your revision sessions from another day. Put like this, it doesn’t look too bad, does it? And yet it’s 25 hours of revision time a week.

Now, write down your subjects on another piece of paper: Physics, Chemistry, Biology, or whatever they are. It’s best if you also write down a list of topics within each subject: Electromagnetism, Waves; Kinetics, Organic Chemistry; Genetics, Photosynthesis, and so on. It’s tempting to start revising the subjects you find the easiest, but think about the subjects and topics you find hardest. What do you need to spend most time on?

Let’s say you’ve got 25 revision slots in a week (five hours a day, for five days a week). And let’s say you are doing three A-levels. All things being equal, that would be 8 or 9 slots each a week. But probably one of your subjects needs more work than the others; no doubt there are some topic areas that you know need more work. Fill them in first, and give them more weight in your timetable.

So, how’s that looking? It may be nowhere near the 50 or 60 hours that your school suggest you do, but, the way you’ve drawn it up, it should be 25 hours of GOOD revision time a week. Just because some people spend longer at a desk with a book or computer screen in front of them doesn’t mean they are spending longer revising, after all. Making the most of revision time is what it’s all about.

Now, all this about a timetable isn’t specific to the sciences – you can apply it to any sort of revision. Which is all very helpful, because you might be doing a mixture of arts and sciences.

Make notes – but not too many

Some people can’t see the point of making notes. They’ve written everything down in their exercise books in the first place – why write it out again? One reason is to get something into your head: the very act of writing something down helps hammer it into your brain.

Another good reason for making notes is that, if you are making CONCISE notes, you have to understand what you are taking notes on. Again, this is worth doing. The more concise your notes are, the less you have to read when you go through them again.

Decorate your walls

Flashcards can come in handy for revision as well. Cut up a piece of stiff paper or thin card into bite-size chunks (you can get about 18 pieces out of an A4 sheet of paper). Now you can write down anything you need to remember particularly: this might be equations, or short sentences, or graphs, or diagrams. Read through them and test yourself. Stick the most important ones on your walls, so you see them every time you are in your room. It might even get to the point where you associate, say, your cupboard door with Newton’s First Law of Motion. That might seem very sad – but it’s helpful, all the same.

Or put up a coloured representation of the Periodic Table on your wall. Again, how sad – but if it helps you learn the elements in Group 1 or Period 3, then that’s great.

Practicals

Obviously, you can’t revise for practical exams at home. But you can look over common scientific methods and techniques from your practicals notebook. You want to be in a position where you won’t be surprised by what you are asked to do in the practical exam.

Do practice papers

You might not think this is a tip, because it’s so obvious, but you can’t beat doing past papers for practice. These should be available from your school or wherever you are; they are certainly available online. And get hold of the answer papers as well.

But don’t cheat when you are doing them. Sit them in exam conditions; make sure you spend the exact length of time that the actual exam will be. Then have a short break, and mark the paper yourself, using the answer sheet.

Here it’s an advantage that you are doing sciences: the answers will clearly be right or wrong, and there’s no room for subjective opinion as there is in, say, history or English literature. Where you’ve got an answer right – well done. Where it’s wrong, have a look at the answer paper, and see if you can work out where you went wrong. If you can, remember this for next time. If you can’t, try and find out how to get the right answer. You may need to ask a teacher or a friend. The same sort of questions crop up year after year, so it really is worth knowing how to answer them.

Mark scheme

Now, the mark scheme is a REALLY annoying aspect of how A-level exams are marked – but you have to be aware of the exact wording that the examiners are looking for. This particularly applies to, say, descriptions of flame tests or the colour of precipitates in chemistry – and of course for many definitions. Your teacher will probably have indicated where particular wording is needed: don’t just think it’s all right to give an approximate wording, because you know what you mean: in certain cases, you have to give the EXACT wording. There’s no other way round this but to play ball and learn the wording off by heart.

Regular testing

If there’s a tame person in your household whom you can call on to test you, that’s great. It doesn’t mean they have to concentrate on you entirely – testing can be done while you are both clearing the table, emptying the dishwasher, cooking the supper or walking the dog. If there’s no such person available, then test yourself, by saying things over to yourself. Talking to yourself isn’t always a sign of madness: it can be the sign of a good reviser too.

Extra reading

Exams are made to test what you have learnt. But – although it’s not actually revision – a bit of reading round the subject can work wonders. Try and do a little bit of extra reading now and then, even if it’s only one or two Science news stories on the BBC website. It may even help illustrate some topic that you have been learning about. If you have the chance to bring in something relevant to an exam question, it will help you stand out from the crowd.

Don’t compare.com

Everybody does it – but it’s not always helpful to compare yourself with what your friends are doing. So, Hermione has spent 60 hours revising Chemistry in the holidays, and you’ve only spent 30? But maybe your 30 are as good as Hermione’s 60. If you apply good revision techniques and self-discipline, then 30 can be just as good as 60.

And not an Auto-Answer Quill in sight.